The Asquith-Stanley-Montagu Affair

A guide to the most significant romantic triangle in British political history.

The Protagonists

H.H. Asquith

"The Prime"

Role: Prime Minister of the UK (1908–1916).

The Obsession: By 1912, he had fallen obsessively in love with Venetia Stanley, describing her as his "pole-star."

"The scales dropped from my eyes..."

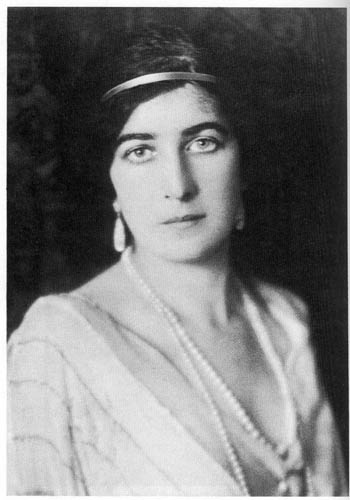

Venetia Stanley

The Muse

Character: Noted for her "masculine intellect," and an "unsurprised" quality that allowed her to absorb shocks.

"Getting the maximum fun out of life."

Edwin Montagu

"The Assyrian"

Role: Financial Secretary; Asquith's former private secretary.

The Conflict: Desperately in love with Venetia, yet tortured by her lack of physical attraction to him.

The Volume

Between 1912 and 1915, Asquith wrote Venetia hundreds of letters. In a single eight-month period in 1914, he calculated he had written no less than 170 letters.

State Secrets

Asquith shared military information, including the shortage of shells, the Dardanelles strategy, and Cabinet infighting—often while sitting at the Cabinet table.

A Note from the Cabinet

"I am writing this at the Cabinet & have to be careful... I was more than disappointed to find no letter! It came, at last – after I got back from the meeting – and was all that I could have wished for..."

— September 4, 1914

The Crisis

How a broken heart may have toppled a government.

The Betrayal: Amidst the "Shells Crisis" and the failure of the Dardanelles, Venetia wrote to Asquith announcing her engagement to Edwin Montagu.

The Consequences: Asquith was "absolutely broken-hearted." Within a week, he formed a Coalition government, ending the last Liberal administration.

The Aftermath

The marriage of Venetia and Edwin in July 1915 did not end the drama; it merely shifted the stage. The years following the "Crisis of May" were marked by political treachery and the slow decline of power.

The Political Rift (1916–1917)

The Fall of Asquith: In December 1916, Asquith was forced out of the premiership by Lloyd George. Edwin Montagu, caught in the middle, tried desperately to mediate.

Margot’s Fury: Margot Asquith wrote that for a man to desert his fallen chief was an act of "political suicide." She refused to see the Montagus for years.

The Private World: Obsession & Escape

The Stolen Photographs

In September 1914, Asquith let himself into Venetia's parents' house solely to "steal" two photographs of her from the table.

The "Annus Mirabilis"

While the world saw 1914 as a catastrophe, Asquith called it a "miraculous year," noting he had hardly gone a day without seeing or writing to Venetia.

The "Pole-Star"

Venetia displaced Asquith's "little harem" of younger favorites to become the person to whom he could write most freely about the most important things.

The Gift of "Unsurprise"

Asquith most valued Venetia's calm—a gift of "unsurprise" that allowed her to take any news, no matter how shocking, in her stride.